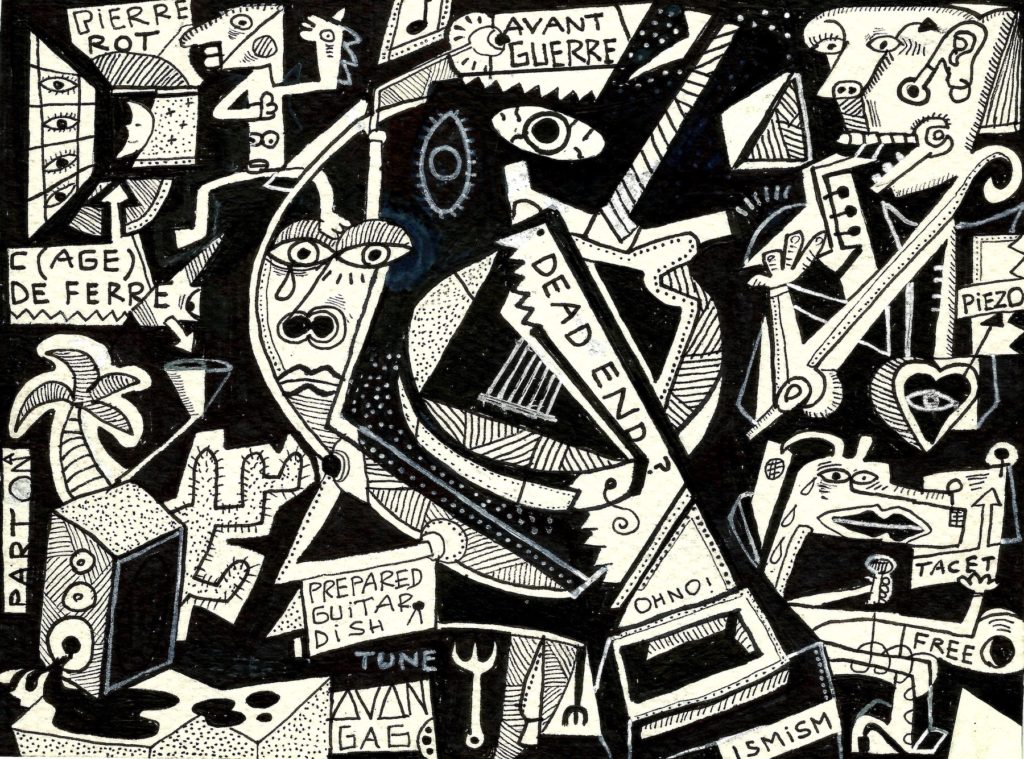

Illustration by Gonzalo Fuentes

An excerpt from Nobody Knows I’m Famous: A Year In Life Of An Unknown Musician

14 July 2016, Thursday

Although I am often labeled as such, I am not an avant-garde musician. In fact, I don’t think there is such thing as avant-garde music any more. Avant-garde, in relation to art, used to mean “cutting edge” and “progressive”; the etymology is French, literally “advance guard” – in a military sense, the first line of troops. Music, in my opinion, hasn’t been avant-garde since the 1950s. One can argue that a few 1960s albums such as Revolver or Trout Mask Replica, or flourishing practices like free improvisation and computer-generated music were avant-garde but you can find all the alleged innovative ideas that are prevalent in those works in recordings from the 1950s, if not earlier.

Sun Ra was experimenting with group (and free) improvisation in the 1950s – hints of his more radical, soon to come, ideas are available on Super-Sonic Jazz. (Goodness, if I wanted to stretch it, I could mention Dixieland music laying the foundation for group improvisation in the early 1900s!) Raymond Scott, whose most famous composition “Powerhouse” found its way into countless Looney Tunes cartoons (and Rush’s “La Villa Strangiato”), was also an electronic music pioneer, inventing and recording with ring modulators, envelope filters, and even electronic drum generators in the 1950s.

Even rock and roll was avant-garde in the 1950s. The intentionally distorted guitar amps of Ike Turner and Paul Burlison (guitarist for Johnny Burnette and the Rock and Roll Trio) synthesized a radical sound, one that was, prior to their recordings, to be avoided. A few blues musicians also recorded with distorted tones around the same time as Turner and Burlison, most notably Pat Hare (listen to his stunning playing on James Cotton’s “Cotton Crop Blues”) and Willie Johnson (with Howlin’ Wolf). However it’s impossible to know who among them was doing it deliberately, as Turner and Burlison did, and who was a beneficiary/victim of poor equipment.

Two last words on the 1950s and the avant-garde: John Cage.

Today, avant-garde is as generic a term as blues, jazz, or metal. Unfortunately it’s a catchall that, to the uninitiated, means anything that isn’t commercial – especially if it is weird, dissonant, or cacophonous. Synonymous appellations – experimental, progressive, fringe, forward-thinking, outsider, etc. – do no better at accurately describing the array of styles found under the leaky umbrella of “avant-garde”.

The semantics and pigeonholing gets worse: If a musician does label his or her music avant-garde, so that a mainstream audience can understand the music in context, other musicians, who a mainstream audience might also deem avant-garde, will say, “Your music isn’t avant-garde! People were doing that 50 years ago!” Damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.

As an alternative I came up with the term “Modern Primitive Guitar” to describe my guitar playing and composition style [for more see Appendix II of Nobody Knows I’m Famous]. I have since broadened that moniker to “Modern Primitive Acoustic Scientist Music” so as to include any non-guitar music I compose. These labels are not helpful in any pragmatic sense but they are more playful and emblematic (and less loaded) than avant-garde.